Scientific Calendar May 2022

Cellular atypia in urine as an indicator of bladder cancer

True or false? Bladder cancer…

mostly affects individuals under the age of 30.

is one of the most common types of cancer in male individuals.

is treated easily by chemotherapy alone.

does not show a high recurrence rate.

is mainly caused by smoking.

requires close post-treatment monitoring by cystoscopy.

Congratulations!

That's the correct answer!

Sorry! That´s not completely correct!

Please try again

Sorry! That's not the correct answer!

Please try again

Notice

Please select at least one answer

Scientific background

Bladder cancer

Bladder cancer is the sixth most common type of cancer in male individuals with a median age of 69 at the time of diagnosis. The main risk factor for developing bladder cancer is smoking, causing up to 65 % of cases in male and 30 % in female individuals. Further risk factors include exposure to chemical substances, predisposition based on ethnicity and gender, medical and family history of bladder cancer, previous cancer treatment, recurrent bladder infection and consumption of well water contaminated with arsenic [1].

In general, bladder cancer can be distinguished in non-muscle invasive (NMIBC) and muscle invasive bladder cancer (MIBC). NMIBC (stages 0 and 1) starts as a carcinoma in situ, where urothelial cells of the bladder are degenerated and develop into a papillary tumour that reaches into the lumen of the bladder but is limited to the urothelium and the lamina propria beneath. MIBC starts with the invasion of the tumour into the muscle layer (stage 2) and further spreading into the fat layer and reproductive tissues (stage 3a) and the proximal lymph nodes (stage 3b). In the final stage, the tumour cells spread across the body and cause the formation of metastases (stage 4) [2]. The prognosis for the survival of individuals diagnosed with bladder cancer strongly depends on the time of diagnosis and declines with progression towards more invasive cancer stages [3].

Since there are no standard programmes in place for the screening for bladder cancer in risk group individuals, bladder cancer is often an incidental finding in the context of bladder cancer-related symptoms, such as abdominal pain and macrohaematuria. The most common diagnostic techniques include urine cytology and cystoscopy, followed by advanced imaging techniques, histopathology, and molecular diagnostics. While urine cytology is a microscopic investigation of urinary cells stained with Papanicolaou or other comparable staining agents, cystoscopy is an invasive, endoscopic procedure to examine the urothelium of the bladder [4].

The options for treating bladder cancer depend on various parameters, including the cancer stage at diagnosis, the size and location of the tumour, and tumour genetics. Treatment options thus range from a transurethral resection (TURBT), chemotherapy, radiotherapy and immunotherapy to a radical cystectomy and are often applied in combination in a multimodal approach [4,5].

Non-muscle invasive bladder cancer shows a high recurrence rate of up to 60 % in the first and up to 70 % in the fifth year after treatment. Therefore, a close surveillance by quarterly cystoscopies is recommended [6].

Atypical cells on the UF-Series

Through fluorescence flow cytometry, the UF-Series allows the detection of atypical cells (Atyp.C) and the differentiation from non-atypical cells in urine specimens. Atypical cells are released from the urothelium and show alterations suspicious of malignancy, including an enlarged nucleus, an increased N:C ratio and increased numbers of nucleoli [7].

The potential of the Atyp.C parameter in the detection of bladder cancer is the subject of scientific investigations. Aydin et al. [8] demonstrated the potential of the UF-Series in combination with the UD-10 to detect urothelial malignancies in a case of a recurrent high-grade urothelial carcinoma in an outpatient setting. Tınay et al. [9] revealed the potential of Atyp.C for diagnostic decisions in the context of bladder cancer surveillance for patients with a known history of bladder cancer, especially with low-risk non-muscle invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC), concluding a potential to reduce invasive cystoscopies on the patients’ side. For patients with a suspected diagnosis of urothelial carcinoma, Ren et al. [10] demonstrated the predictive power of Atyp.C in good agreement with cytopathology, concluding a potential as an accessory test for urothelial carcinomas in the context of routine urinary diagnostics.

Disclaimer:

The Atyp.C parameter is intended for research use only.

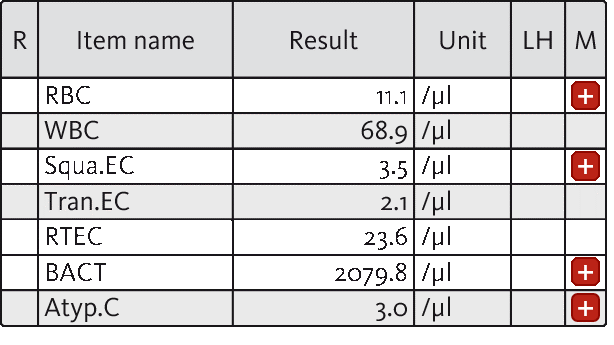

Numerical results

In the present case, a 69-year-old male patient reported to the clinic with symptoms of a urinary tract infection, including light fever and dysuria. For clarification of the symptoms, an initial urinalysis screening was ordered. Upon investigation of a urine specimen on the UF-5000, the suspected UTI was confirmed by the presence of 2079.8 bacterial cells per µL, accompanied by mild haematuria and leucocyturia.

In addition, laboratory analysis revealed the presence of 3.0 atypical cells (Atyp.C) per µL. Microscopy analysis including the UD-10 confirmed the presence of atypical cells with large nuclei and prominent nucleoli. Based on these findings, cystoscopy was conducted, supporting the urinalysis findings and leading to the diagnosis of bladder cancer.

Conclusion

Urinary flow cytometry bears the potential to detect malignant cells in the context of urothelial carcinomas and might be applied in the detection of bladder cancer, especially in the surveillance of known bladder cancer patients, by recognising urinary atypical cells, aiming to reduce the frequency of invasive cystoscopies.

References

[1] Torre LA et al. (2015): Global cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin 65(2):87–108.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25651787/#:~:text=Based%20on%20GLOBOCAN%20estimates%2C%20about,65%25%20of%20cancer%20deaths%20worldwide.

[2] Sanli O et al. (2017): Bladder cancer. Rev Dis Primers 3:17022. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28406148/

[3] Ripoll J et al. (2021): Cancer-specific survival by stage of bladder cancer and factors collected by Mallorca Cancer Registry associated to survival. BMC Cancer 21:676. https://bmccancer.biomedcentral.com/track/pdf/10.1186/s12885-021-08418-y.pdf

[4] Lenis AT et al. (2020): Bladder CANCER – a Review: JAMA 324(19):1980–1991. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33201207/

[5] Ploussard G et al. (2014): Critical Analysis of Bladder Sparing with Trimodal Therapy in Muscle-invasive Bladder Cancer: A Systematic Review. Eur Urol 66(1):120–137. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24613684/

[6] van der Heijden and Witjes (2009): Recurrence, Progression, and Follow-Up in Non-Muscle-Invasive Bladder Cancer. European Urology Supplements 8:556–562. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1569905609000578?via%3Dihub

[7] Mokhtar A et al. (2010): Diagnostic significance of atypical category in the voided urine samples: A retrospective study in a tertiary care center. Urol Ann 2(3):100–106. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20981196/

[8] Aydin O (2021): Atypical cells parameter in Sysmex UN automated urine analyzer: feedback from the field. Turk J Biochem; Diagnostic Pathology 16:9. https://diagnosticpathology.biomedcentral.com/track/pdf/10.1186/s13000-021-01068-5.pdf

[9] Tınay İ et al. (2020): “Atypical Cell” Parameter in Automated Urine Analysis for the Diagnosis of Bladder Cancer: A Retrospective Pilot Study. Bull Urooncol 19(1):17–19. http://cms.galenos.com.tr/Uploads/Article_36890/UOB-19-17-En.pdf

[10] Ren C et al. (2020): Investigation of Atyp.C using UF-5000 flow cytometer in patients with a suspected diagnosis of urothelial carcinoma: a single-center study. Diagn Pathol 15(1):77. https://diagnosticpathology.biomedcentral.com/track/pdf/10.1186/s13000-020-00993-1